"I Have A Dream"

In just a few days we honor the life and legacy of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr.

The year was 1964, and President Lyndon B. Johnson had just signed the new Civil Rights Act. It created anger, violence, and resistance. Now the future of the South hung in the balance. Tensions ran high.

The Ebenezer Baptist Church in downtown Atlanta was crowded that afternoon in 1968, filled beyond capacity for the funeral of Martin Luther King Jr. Reporters came from all over the world, standing shoulder to shoulder with mourners who had come not to observe history, but to grieve a man who had given his life to peace, justice, and equality. Women did not cover the hard news in this era - but somehow I was there to tell the world of this tragic event.

Inside the sanctuary, sorrow settled heavy in the air—tempered by hymns, prayer, and the unmistakable sense that something sacred and irrevocable was taking place.

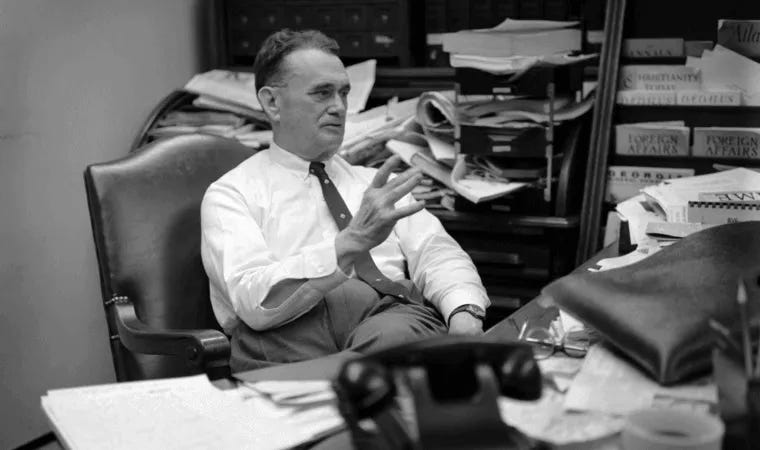

I had been honored to welcome the Pulitzer Prize winner, the late Ralph McGill, publisher and editor of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, to join me at WSB on many occasions to discuss the Civil Rights Movement raging across the South. McGill used this powerful platform and his own to expose the human cost of segregation, earning him the enduring nickname the Conscience of the South. At a time when silence was expected—and rewarded—he stood almost alone, breaking the white code of polite avoidance around racial discrimination and segregation.

McGill paid a steep personal price for that courage. He endured constant threats—burning crosses planted on his lawn in the dead of night, bullets fired into his home, and homemade bombs left in his mailbox. Intimidation was meant to silence him. Instead, it revealed just how dangerous truth-telling had become in the South he was determined to change. His moral courage and unwavering conviction stayed with me. When the moment came to report on the death of Martin Luther King at this momentous event, I drew strength from the example he had set—steady, fearless, and guided by a belief that telling the truth mattered, even when it came at a cost.

While covering news in Atlanta there was never a story as prodigious as the struggles for racial equality in the South. Witnessing the inhumanity toward the black population is something I will never forget. Unthinkable incidents during this harrowing time included those of the Governor of the State of Georgia, Lester Maddox.

Maddox threatened three young black seminary students at gunpoint for attempting to enter his racially segregated Atlanta restaurant, The Pickrick. He pulled his pistol and pointed it at them, saying, “Get the hell out of here, or I’ll kill you.” Rather than help the customers being held at gunpoint, the white patrons eating at the restaurant grabbed ax handles and chased them into the parking lot, threatening violence.

King’s Close Ties with the Lowcountry

King visited St. Helena’s Frogmore community 5 times between 1964 and 1967. At that time, the Penn Community Center had been established as a place of safety, a place of refuge, a place of restoration for black and white progressives fighting institutionalized Jim Crow racism at great personal risk. It was one of the few places blacks and whites could gather or spend the night together.

The magistrate said, “It was a hush-hush kind of thing; we certainly did not want anything to happen to him while he was here.”

It was a dangerous mission, risking his life for his people, standing against the Ku Klux Klan, and seeking peace and justice during the agonizing days of the Civil Rights Movement.

Time spent at Penn Center was to be a time of relaxation for the man who was the figurehead for America’s red-hot civil rights movement, the Nobel Peace Prize winner, and the “I have a dream” icon. Here was a place where he could rest in a safe, secluded corner of South Carolina in a simple wooden cottage named for Hastings Gantt, an all-but-forgotten former slave.

The link between these two men who never knew each other was sealed when President Barack Obama signed a proclamation establishing the Reconstruction Era National Monument in Beaufort County.

Remembering a slave named Gantt

Gantt was a hero of his era. Once a free man, he bought land, raised cotton, made money, and continued to buy more land. He was repeatedly elected to the state House of Representatives and gave 50 acres to the Penn School, allowing it to grow from its beginnings in 1862 as one of America’s first schools for freed slaves.

Mike Cooke via mg2.substack.com

10:53 AM (1 hour ago)

to me

Hello Pat

We were not living in America at the time. We heard about Martin Luther King Jnr in Britain as well as the civil rights movement. Later, when we came to live in America in 1989, I read a huge book chronicling the History of The American People’s. As in my home country, going back a few hundred years, some of it makes sad reading.

Let’s hope we will continue to move on with equality and tolerance for all mankind, not just in America, but throughout the world. For the sake of our Grandchildren!

Another beautifully written letter Pat, and, as always, very insightful.