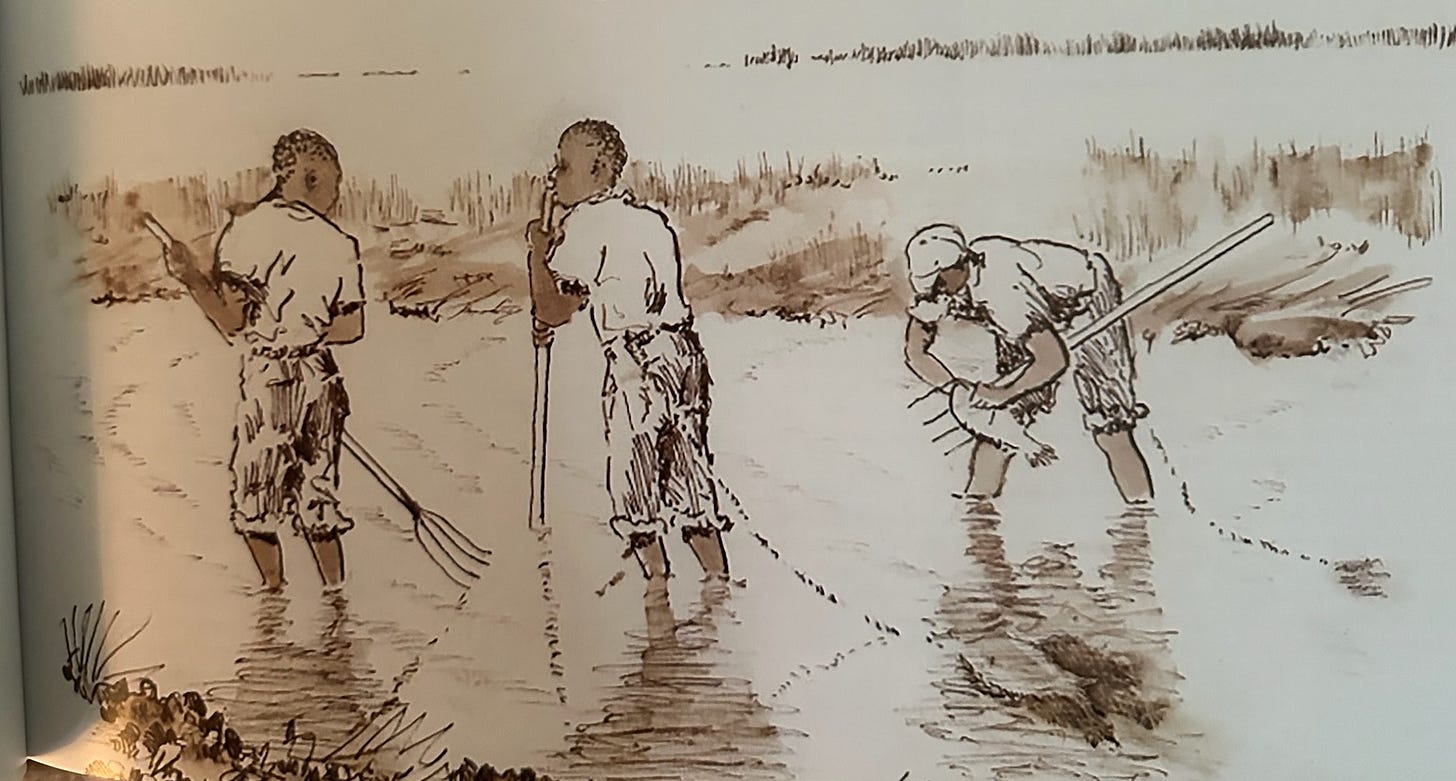

Pitchforking for Flounder on the Barrier Islands

A beloved storyteller and artist come together.

The most inspiring moments in my writing life have never come from awards or deadlines, but from the people I meet along the way — the chefs, the creatives, the entrepreneurs, and lovers of life, our watermen who rise with the tides, and our artists who see beauty where the rest of us might pass by. They are the ones who give my work its heartbeat, reminding me that stories are everywhere, waiting to be noticed.

This story brings together two of my most admired Lowcountry figures — the late writer and sportsman Pierre McGowan and artist, the beloved Doug Corkern of Bluffton. I’ve read and collected every book Pierre ever wrote and have been fortunate to work with Doug over the years, but I never imagined I would one day own one of his pieces.

To see it there on Christmas morning was deeply moving — a gift from someone who truly understands my love of art and recognizes Doug’s remarkable ability to capture the faces of everyday people and let them live on, long after the moment has passed. I am so grateful for such a thoughtful and meaningful gift, one I will cherish always.

Here is sportsman Pierre McGowan’s remarkable story.

Between St. Helena Sound and Port Royal Sound, a necklace of eight barrier islands stretches along the South Carolina coast, just beyond Beaufort. Two miles north lies the southern shore of St. Helena Island—salt-washed, quiet, and deeply rooted in time. It was here, at the water’s edge, that the late Pierre McGowan grew up, shaped by tides, mud, and moonlight.

Pierre’s father, Sam, was the rural mail carrier for St. Helena Island, a man who trusted the rivers enough to let his young sons navigate them day or night. His mother, no doubt, lay awake through many of those nights, listening for sounds she could not hear and trusting the water to return her boys safely home.

For nearly eighty years, Pierre fished and hunted these rivers and tidal creeks. By the time I came to know him—after decades of living in Beaufort—Pierre was already a local legend. Everyone knew him. Everyone loved him. He had the rare gift of storytelling that made you feel as though you were standing right beside him, knee-deep in pluff mud, lantern light flickering across the water.

“Spending money was scarce during the Great Depression,” Pierre once told me. “We had to find ways to earn a little cash. The easiest way for me was right out in the creek in front of our house.”

In those days, vast oyster beds stretched across the water in front of Pierre’s home, laced with narrow tidal creeks exposed at low tide. This area—known historically as the Harbor River Flats—extended east toward Coffin Point for nearly five miles, sometimes only a few hundred yards wide, sometimes opening out to nearly a mile. When the tide fell, those creeks became hiding places for flounder, tucked into mud and silt, waiting for the water to return.

After feeding on finger-length mullet, flounder bury themselves, nearly invisible, trusting the tide to lift them again.

“When the tide is ebbing,” Pierre said, “the water gets muddy, and the flounder can’t see what’s coming. That’s when a two-legged predator with a pitchfork has the advantage.”

That predator was often Pierre himself.

The practice is called pitchforking—an old, ingenious method of fishing believed to have originated during slavery and passed down through generations. Pierre learned it as a teenager from older Black fishermen who knew the creeks intimately. It wasn’t sport then. It was survival.

“Often,” Pierre said quietly, “this was the only way we could put food on the table.”

Pitchforking requires nerve and trust in the dark. The fisherman wades through muddy water, blind-gigging the bottom with a pitchfork or gig—a five-pronged spear fixed to a lightweight pole. The darker the night, the better. In the 1940s, Pierre and his brothers carried gas lanterns, their glow barely cutting through the blackness.

When the pitchfork strikes, the fisherman feels it before he sees it—a faint quiver in the handle. It might be a flounder. It might be a stingray. There are no barbs on the fork, so the fish can slip free if you’re careless. The trick, Pierre explained, is to slide your fingers gently into the gills while lifting the fish and pitchfork together, steady and calm. Then the flounder goes onto a stringer, the other end tied securely to your belt, trailing behind you like proof of patience and skill.

On many Friday nights, Pierre and his two brothers slipped away from the house at dark and returned home near two o’clock Saturday morning, their stringers heavy—seventy-five to a hundred flounder between them. They were choosy about where they sold their catch. Door to door, they went, only in Beaufort’s most aristocratic neighborhood: The Point.

Word traveled fast.

Residents would be waiting at the sidewalk, metal dishpans in hand. A five-pound flounder could fetch fifty cents—a small fortune to three boys who had earned every dime with mud on their legs and salt on their skin. In just a couple of hours, the fish would be gone, and three very happy boys would head back toward St. Helena Island under the fading stars.

Today, pitchforking still survives in the creeks and rivers of the Lowcountry. Natives and newcomers alike slip into the water on dark nights, following the same rhythms Pierre learned as a boy. It is more than a way to catch fish.

It is a conversation with the tide, a tradition carried forward by moonlight, memory, and the quiet knowledge of life by the water’s edge.

Marjorie Kennan Rawlings wrote about gigging for what she thought were flounder but were rays instead.