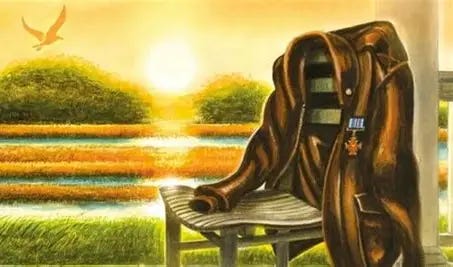

Remembering Pat Conroy

Ten years after his death, we continue celebrating his life and legacy.

This week, Pat Conroy would have turned eighty. It was here, in our small salt-misted town of Beaufort, where the son of a Marine fighter pilot—immortalized as The Great Santini—finally found his soul.

At the “Conroy at 70 Literary Festival,” the town that shaped him opened its arms once more to celebrate the man who had, in turn, given it immortality through words. His wife, the novelist Cassandra King Conroy, said wistfully, “I wish that he could have lived to be a grumpy old man.”

Beyond the annual festival, the Pat Conroy Literary Center carries his spirit forward—hosting more than a hundred events each year and drawing some 4,000 visitors who come seeking that same rare blend of grace, humor, and raw truth that defined his work.

If only I had told him how much he’d helped me—how his simple advice, “Write what you know,” gave me courage to keep going. The Water Is Wide changed my life the first time I read it—and every time after that. I must have read it a dozen times. No other writer has shaped my own voice more profoundly.

A Chance Meeting at the May River Grill

It was 2011, and I had just released Shrimp, Collards, and Grits—my first collection of stories, recipes, and fine art celebrating the creeks and gardens of the Lowcountry. The book had been created in honor of Beaufort’s Tricentennial, a love letter to the land that shaped me.

Elizabeth Millen, founder and publisher of Pink Magazine, invited me to lunch at the May River Grill for an interview. Knowing it would be lively, I brought my husband, Cloide, and my daughter, Margaret, along for the fun.

We had just settled into our table when I looked up—and there he was. Pat Conroy himself was walking through the door with his lifelong friend Bernie Schein. Elizabeth, Margaret, and I exchanged glances and whispered, “Let’s not bother them.”

But if you knew my husband, you’d know that was never going to happen. Cloide never met a stranger, and he wasn’t about to start that day.

Pat later wrote about that day in The Death of Santini, recalling the chance meeting at the May River Grill and how we’d struck up conversation as though we’d known one another all our lives. That was Pat’s gift—he had a way of making everyone feel like an old friend. He wrote about Cloide’s easy charm, how quickly laughter filled the table, and how the conversation drifted—as it always does in the Lowcountry—from food to faith to family.

When I later read his account, which was a total surprise, I smiled through tears. There it was in print—our ordinary lunch turned into a scene from a Conroy novel, complete with the warmth, humor, and humanity that colored all his pages. To see our names there, caught in the swirl of his storytelling, felt like a small benediction.

What Pat did better than anyone was to take real life and lift it to the level of art. He showed us that our own stories—our struggles, our flawed families, our love for this Southern soil—were worth telling. He reminded us that truth, even when it hurts, is what makes writing holy.

Every time I pass the Pat Conroy Literary Center or walk along the Beaufort River, I think of that afternoon. The sunlight slanting across the water, the laughter echoing over lunch, the way stories wove us together like tidal creeks converging at high tide.

He once wrote, “The most powerful words in English are ‘Tell me a story.’’

Thank you, Pat, for telling ours—and for teaching me how to tell mine.

(From pages 49 and 50) This is Pat’s writing from The Death of Santini

“Several months later, I was sitting in the May River Grill in Blufton when a feisty, combative man approached my table. I rose to introduce myself to him. He had the terrific Southern name of Cloide Branning and told me his wife wanted to give me a copy of her new cookbook, “Shrimp, Collards and Grits.

“It has my name written all over it, Cloide,” I said. His table came over to my table, and his wife, Pat, signed one of her books for me - a beautifully bound and boxed book that would look handsome in any kitchen. Their pretty young daughter has begun her teaching career on Hilton Head and had just finished reading The Water is Wide. I told the young teacher that I was twenty-five years old when I started writing that book and had reached the age when I did not listen to anything a twenty-five-year-old, snot-nosed kid had to say.

“You had a lot to say and you said it well,” she replied.

“Thank you so much,” I said.

“I played golf once a week with Walter Trammell,” Clide said, with mischief in his eyes.

“I hear my superintendent was a very good golfer,” I said, puzzled.

“Well, you ruined his whole life. That’s just for starters. When your book and movie came out, he became one of the most hated men in America. The same school board that fired you fired him a couple of years later- what you did to him haunted him to his death.”

“I used to have nightmares about Walter Trammell,” I said.

Cloide said, “You whipped his ass, and Trammell knew it and did the whole town.”

“Good. I couldn’t be happier. But his golf game?”

“Every time we went out to a golf course, he would get ready to tee off on the first hole,” Cloide explained. “Walter would begin his backswing, and I’d say, ‘Pat Conroy,’ and his arms would palsy up and begin shaking - they would actually spasm when I said your name. It ruined his golf game.”

Such a beautiful tribute to this talented author. What an honor it must be that your experience meeting Pat Conroy made it into his writing.

Thank you, Pat, this was wonderful. I wish I could have known him better. I was honored to be the soloist for Pat Conroy's funeral and sang at the opening of his amazing Literary Center. The world will never know another like him. We will treasure Mr. Conroy forever. 💜