[I grew up in Maryland but just outside Washington, DC, away from the Chesapeake Bay, and it was only as an adult that I discovered the Eastern Shore, the most particular and wonderful part of the state. I wrote this portrait of the region in 1992, and I’ve debated whether I should publish it again now, worried that it was dated. But being dated is perhaps a virtue; it would be difficult or impossible to write a similar piece now. It’s also a lost piece that appeared in just a few thousand print copies, and you’re unlikely to find its insights into crabs, especially soft-shells, anywhere else. A bit of good news since I wrote is that efforts to restore Bay’s oysters seem to be having some success. On the other hand, partly as an effect of the warming climate, the blue crab population has declined, though recently it has been holding steady. And sadly, some of the land and islands of the Eastern Shore are so low that they’re in danger from rising water. Not just the culture but the place itself is somewhat disappearing. (The original article has been lightly edited.)]

THE RAGGED SHAPE CUT FROM MARYLAND and Virginia by the Chesapeake Bay is about two hundred miles long and only thirty miles wide at its widest. The Bay is shallow; the average depth in open water is only 27 feet — 21 feet counting tributaries — and it tapers into an expansive fringe of marsh. The shallowness allows great meadows of underwater grasses to grow; these, the marshes, and the graduated salinity from north to south together produce an exceptionally diverse and prolific range of plants and animals. The Bay may be the most biologically productive estuary in the world. It’s famous for oysters, crabs, rockfish (as striped bass are called around the Bay), canvasback ducks, and terrapins. Blue crabs are native to the Atlantic coast from Maine to Argentina, but nowhere do they occur in such profusion as in their ideal surroundings in the Chesapeake Bay. Their sweet meat is the last of the Bay’s once-lush seafoods to persist in healthy abundance.

The submerged grasses — mostly eelgrass — are home or nursery to innumerable creatures, from microscopic herbivores to large carnivores. Among those eaten by humans are blowfish, bluefish, spot, silver perch, pinfish, tautog, summer flounder, red drum, weakfish, croaker, striped mullet, shrimp, and blue crabs. The crabs are indiscriminate scavengers of decaying organic matter, plant or animal. The eelgrass itself is food for many fish, for waterfowl, such as canvasback ducks, and even for marsh rabbits (muskrats, a sometime Eastern Shore meat). Beds of eelgrass hold more species, and more of each one, than surrounding waters.

The 4,400 square miles of the Bay set apart the Delmarva peninsula, which contains parts of Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia. The peninsula, especially the major part that looks toward the Bay, is most often called simply the Eastern Shore. It’s there that the land is least spoiled and that the largest concentration of watermen — as those who make a living from the Bay are called — continue to work more or less as they have always done.

Watermen catch crabs on trot-lines baited usually with eel; or they use pots made of heavy chicken wire or pound traps of the same material, running out from the shoreline; or they “scrape” the eelgrass; and in Virginia in winter, they dredge. (Dredging crabs is illegal in Maryland, and it’s probably unwise to dredge so many in Virginia.) Maryland permits crabbing from April 1 to December 31, but cold water makes the actual season shorter. Counting the crabs dredged from their winter retreats in Virginia bottom mud, the season for eating fresh Bay crabs is year-round.

The spring crab runs start in April around Cape Charles in Virginia and move northward as the water warms and the crabs migrate up from the depths and up the Bay into shallower water. The biggest run occurs in mid-May, at the time of the first full moon according to some watermen, though one biologist’s careful record-keeping shows no correlation. The next biggest run is in August.

As a blue crab grows over a life span of no more than three years, it must shed its shell about 20 times. During that brief moment, it becomes soft-shell crab for us to eat. The soft crab season runs from the end of April to September. Before they shed, crabs hide in a protected spot, because afterward the limp crab will be eaten by any predator that finds it, even a hard blue crab.

Once a crab is caught, its claws are “nicked” by the crabber — the tips are broken so it can’t bite — and it’s generally sorted by size and by sex, as shown by the apron on the underside of the crab. Females have red-tipped claws and triangular aprons, and males have T-shaped ones. Females are called “sallies”; the males are “jimmies.”

A sally is ready to mate when she sheds for the last time. A female mates only once, while a jimmy mates repeatedly as opportunity allows. Following subtle underwater signs, the jimmy locates and clings to the top of the female, who folds her claws and allows herself to be carried for two days or more before she sheds; the pair are known as doublers. The jimmy finds a refuge for them, in eelgrass if it’s available. After the sally sheds (so that her apron is soft and will fold back) and the six to twelve hours of copulation are over, the male continues to cradle the soft female for another two days until her shell hardens. The sally is now a “sook.” Afterward she heads toward the Virginia capes at the Bay’s lower end, where she spawns the following spring, releasing as many as two million fertilized eggs. At the end of that summer, the mother crab swims out to the ocean to die. (The lives of crabs and crabbers are nowhere so well and empathetically described as in William Warner’s Beautiful Swimmers.) Sometimes, as in 1972 with Tropical Storm Agnes, a flood of fresh water washes innumerable tiny crab larvae out to sea, where they are lost. But crabs confound predictions and in 1973 they promptly rebounded.

Crabs that are ready to molt are called “peelers,” a state revealed by the color of a fine white-to-red line on the swimming fins — the hindmost of the five pairs of legs. A red line indicates that shedding is imminent. When the peeler’s shell breaks open, it becomes a “buster.” Sometimes busters get “hung” on a part of the shell and they die; sometimes they leave a claw behind, which isn’t a permanent loss because a crab can grow a new one. The emerged crab is, incredibly, a third larger than its just-discarded shell. During the next hour, the crab increases in size yet another quarter to a third. Immediately, the carapace begins to harden by drawing calcium from the salt water. After about six hours, the crab is a “papershell,” still officially soft; at eight to ten hours, the crab is a “buckram,” too crunchy to eat. In twenty-four hours the crab is again hard.

Until a decade ago, oysters and not crabs were the Bay’s most valuable catch. Oysters have declined precipitously since 1884, when oyster-dredging reached its peak. The harvest that year was twenty million bushels. There was some crabbing and other commercial fishing at the time, but oysters were the most suitable for sending by rail and steamship, after mechanical refrigeration made it possible to produce artificial ice. A remarkably detailed picture of the fishing was compiled in connection with the 1880 census. The Maryland oystering portion of the multi-volume Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States (1884–87) was written by Richard H. Edmonds, who had a difficult time assembling his statistics, because oystermen weren’t necessarily inclined to get licenses or report their catches. He wasn’t happy with much of what he found out:

Dredging in Maryland is simply a general scramble, carried on in 700 boats, manned by 5,600 daring and unscrupulous men, who regard neither the laws of God nor man ... Many of the boats are owned by unprincipled men, and I am informed that a number of them are even held by the keepers of houses of ill-repute. An honest man who complies with the law by not working on Sunday, at night, or on forbidden ground, will take at least a week longer to catch a load of oysters than one who, disregarding the law, gets his oysters whenever or wherever he can. The first captain, upon his return, is informed in language more forcible than elegant that unless he makes as quick trips as the second captain his place will be filled by some one less scrupulous.

Edmonds concluded that the Baltimore crews “form perhaps one of the most depraved bodies of workmen to be found in the country,” although some Eastern Shore watermen were “respectable and honorable.” Most had been converted to fervent Methodism, as the churches of the Eastern Shore still attest, and more of them had families. Edmonds noted that a number of the Bay’s oystermen were Black. The oystermen weren’t the only problem.

I have been informed. . . that during a late political canvass for the [Virginia] State legislature one of the candidates, in an address to the oystermen, promised, upon condition of their voting for them, that should they desire to break any of the oyster laws, he, as a lawyer, would defend them free of cost. My own observation leads me to believe that this is by no means an exceptional case.

The laws had been enacted because oystermen had been dredging nearly every oyster from an area of beds before moving on to a new area and stripping it. Takings were lush, but there was a fear the oysters might never recover. Watermen believed they had a God-given right to anything they could plunder from the Bay, a philosophy that may linger here and there in the present. Edmonds was offended that the watermen didn’t have to work harder to get by.

A tongman can at any time take his canoe or skiff and catch from the natural rocks a few bushels of oysters, for which there is always a market. Having made a dollar or two, he stops work until that is used up, often a large part of it being spent for strong drink ... He can readily and at almost no expense supply his table in winter with an abundance of oysters and ducks, geese, and other game, while in summer fish and crabs may be had simply for the catching. So long as they are able to live in this manner it is almost impossible to get them to do any steady farm work.

The upper half of the Bay is dominated by the Susquehanna River, which supplies almost half of the Bay’s fresh water. In glacial times, the present Bay was part of the Susquehanna valley, which gradually filled as the glaciers melted, assuming its current shape only three thousand years ago. Today, water flows into the Bay from nearly all of Maryland, much of Delaware, some of West Virginia, two-thirds of Virginia, about half of Pennsylvania, and a significant part of New York, a total area of 64,000 square miles. By comparison, the whole of Delaware isn’t quite 2,000 square miles.

The quality of the Bay’s water has been falling for decades as the population around it has risen. Whatever enters the watershed’s streams and rivers — eroded soil, farm manure or fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, industrial chemicals, particles from airborne pollution, sewage and anything put into a sewer — runs into the Bay. Because of the Bay’s pattern of circulation, almost none of the harmful substances that enter the Bay leave it. The shallowness that historically made the Bay so luxuriant makes it vulnerable now; compared with other great bays, it contains very little water to dilute the harmful things that flow in. Watermen and biologists used to welcome a rainy year for the nutrients that were washed into the Bay, but today the Bay is menaced by a surfeit of nitrogen and phosphorus from agriculture, sewage, and polluted air. Those two nutrients feed exaggerated growths of algae that keep sunlight from reaching the seagrasses below, eventually killing them. And as the algae die, they fall to the bottom and decay, using up the water’s oxygen and depriving the creatures that need it. Excess nutrients have so far eliminated about 90 percent of the Bay’s underwater grasses. The very flow of fresh water that the Bay needs to maintain its circulation and graduated salinity kills it a little with each rain.

The oyster population is now about 1 percent of what it was one hundred years ago, and oysters may be eliminated entirely. The effect of historical overharvesting has been worsened by poor water and in the last few years by the diseases MSX and dermo, whose rise is surely connected to pollution. Natural oyster beds are built of great accumulations of oyster shells and are known to watermen as “rocks”; they act like coral reefs, providing a home for many other species. It has been calculated that in their original numbers oysters filtered most of the water in the Bay every few days, producing its once-clear waters. (When Captain John Smith arrived in 1608, he could see the bottom at a depth of fifty feet. He was the one who first called the eastern shore the Eastern Shore.)

No one has firm numbers on the elusive terrapin, an old symbol of Maryland food. It is legal to catch terrapins, and there are a few old-school restaurants that buy them. Terrapins dislike people and are losing some of the secluded territories they require for laying their eggs, which are vulnerable to being dug up by dogs or by raccoons, whose populations rise wherever humans move in. With the loss of the seagrasses, canvasback ducks are so few that it is illegal to shoot them. (After the wild celery that used to grow in the low salinity of the upper Bay died, it’s said that canvasbacks never tasted the same.) In the 1950s, Canada geese successfully switched to gleaning Eastern Shore grain fields. Geese had constituted less than a fifth of Bay waterfowl, and now they are two-thirds. In the air and water, just a few of the most adaptable species have come to dominate.

Unfortunately, people are particularly drawn to live and work along the biologically prolific margins between land and water. Half the watershed’s wetlands are already gone. The greatest threat at present comes from the proposed federal definition of a “wetland”; as one biologist puts it, under the definition a wetland doesn’t qualify as a wetland. (The Chesapeake Bay Foundation estimates that 60 percent of Maryland’s wetlands wouldn’t qualify.) And federal and state regulations contain other loopholes that result in a slow loss year by year. Wherever they remain, the wetlands and forest lining the Bay and its tributaries absorb sudden influxes of water from storms, reducing freshwater torrents flowing into the Bay and slowly releasing water during dry periods.

The Chesapeake Bay ecosystem produces an extraordinary self-sustaining wealth in the form of food, livelihood, and recreation. Losing the Bay isn’t cheap. Conversations about the future of the Bay turn sooner or later on the problem of “too many people” — an ever-rising population that is spread more evenly over the land than in the past, blurring the distinction between rural and urban. Any optimism must be based on the possibility of containing the impact of so many people. To save the Bay, or any body of water confronted by a large population, we have no choice but to support agriculture that shuns toxic chemicals and ensures that no nutrients are applied that will be washed from the soil. We have to reduce and concentrate populations so as to preserve large natural and rural areas. And we have to plan the future use of our land using the most advanced knowledge we have.

There are some encouraging trends. Fishing bans have somewhat revived shad and rockfish. The ban on DDT has brought back ospreys and eagles. Banning phosphate detergents has helped to reduce the amount of phosphorus entering the Bay. But most of the needed cures are more complex than bans. Strong cooperative action is required throughout the watershed, and the likelihood of citizens and governments coming together is so small, even with all the talented people at work, that it seems likely the Bay will only get worse. But losing it is unthinkable. Anyone living in the watershed must join the effort to make it better.

In July, 1952, the isolation of the Eastern Shore was breached by the Bay Bridge, which spans the narrow point of the Bay near Annapolis. The eastern end of the bridge rests on Kent Island, site of Maryland’s first English settlement in 1631. US route 50 runs from the bridge halfway down the peninsula, before it turns toward the ocean; US 13 takes over and heads south to the Virginia part of the Eastern Shore and the Bridge-Tunnel built in the 1960s to link the tip of the peninsula with Norfolk on the mainland. Driving along the two highways, you see only strips of commercial development and the flat agricultural landscape of the center of the peninsula, unrelievedly hot in summer. Plowing reveals the strange-looking gray soils. Only by leaving routes 50 and 13 do you one discover small towns and the proximity of water. The side roads are indirect or end on a point or island; many roads are poorly marked and not all appear on a map.

Beyond Kent Island on US 50, one of the first turn-offs leads to the sleepy crossroads of Wye Mills. Just past the four-hundred-year-old Wye Oak, on the right, is the sign for Mrs. Orrell’s Maryland beaten biscuits. For the sake of history, they are probably worth a try, but to me the floury beaten biscuit is testimony to the virtues of yeast-raised bread. Maryland biscuits are made from only flour, salt, lard, water, and now sometimes baking powder; they differ from other Southern beaten biscuits in their smooth upright shape, like a small hen’s egg, usually with a pattern pricked in the top by a fork. The dough is traditionally beaten for twenty to thirty minutes — use of a flatiron, wooden club, hatchet, and axe have all been recorded — until the dough blisters and pops. A few people are said to still occasionally beat biscuits this way. The hot climate made yeast a rarity in many households, and, before there were baking powders, beating softened the biscuits. Eventually a machine was devised to do the work, and presumably that’s what Ruth Orrell uses today.

More than one sign along the road in Talbot County indicates that a farm or manor was settled in the 1650s. A number of long, tree-lined drives lead to unseen houses, closer to the water than the road. The breadth of the Bay once isolated the Eastern Shore from the rest of the world, but navigating the edge of the Bay and its rivers tied the Eastern Shore together. A remnant of the past, the small Oxford-Bellevue ferry, still runs back and forth on the Tred Avon River during daylight hours. In some areas, the mosquitoes are oppressive. And there’s little evidence of air-conditioning; watermen aren’t well off. The accent and dialect of some requires interpretation to be fully understood. A western shore Marylander who married into the Eastern Shore told me that an outsider won’t hear the strongest dialect, because those who speak it don’t like strangers and are silent in front of them. But the people that I’ve met on the Eastern Shore were all friendly and outgoing.

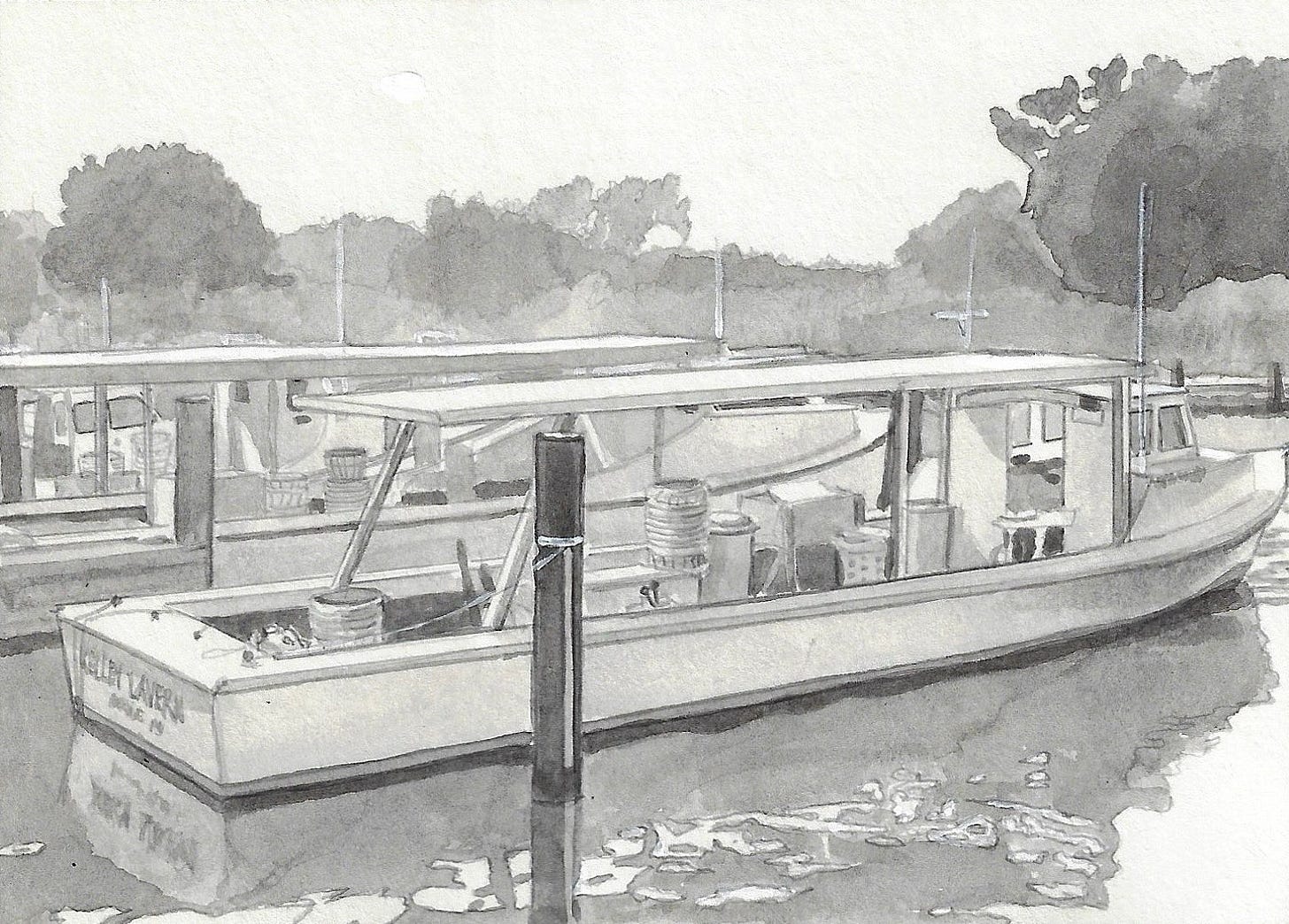

There are about 7,000 watermen in Maryland and another 5,000 in Virginia, with only a few women among them, though the wives of crabbers are often involved with the shedding of soft crabs. A waterman used to live close enough to his boat to walk back and forth every day. Some still do, but as a rule watermen drive pickup trucks, generally with a stack of bushel baskets in back for crabs. Their boats are practical in appearance and meticulously white, rinsed clean at the end of each day with buckets of water. A while ago at Tilghman’s Island I spoke to a young waterman who works as a truck driver in winter, when formerly he would have been going after oysters. He’s lucky, because there isn’t much work to be had away from the water. House-painting was the main alternative, he said, explaining that most watermen dropped out of school and feel they can’t do anything but work on the water.

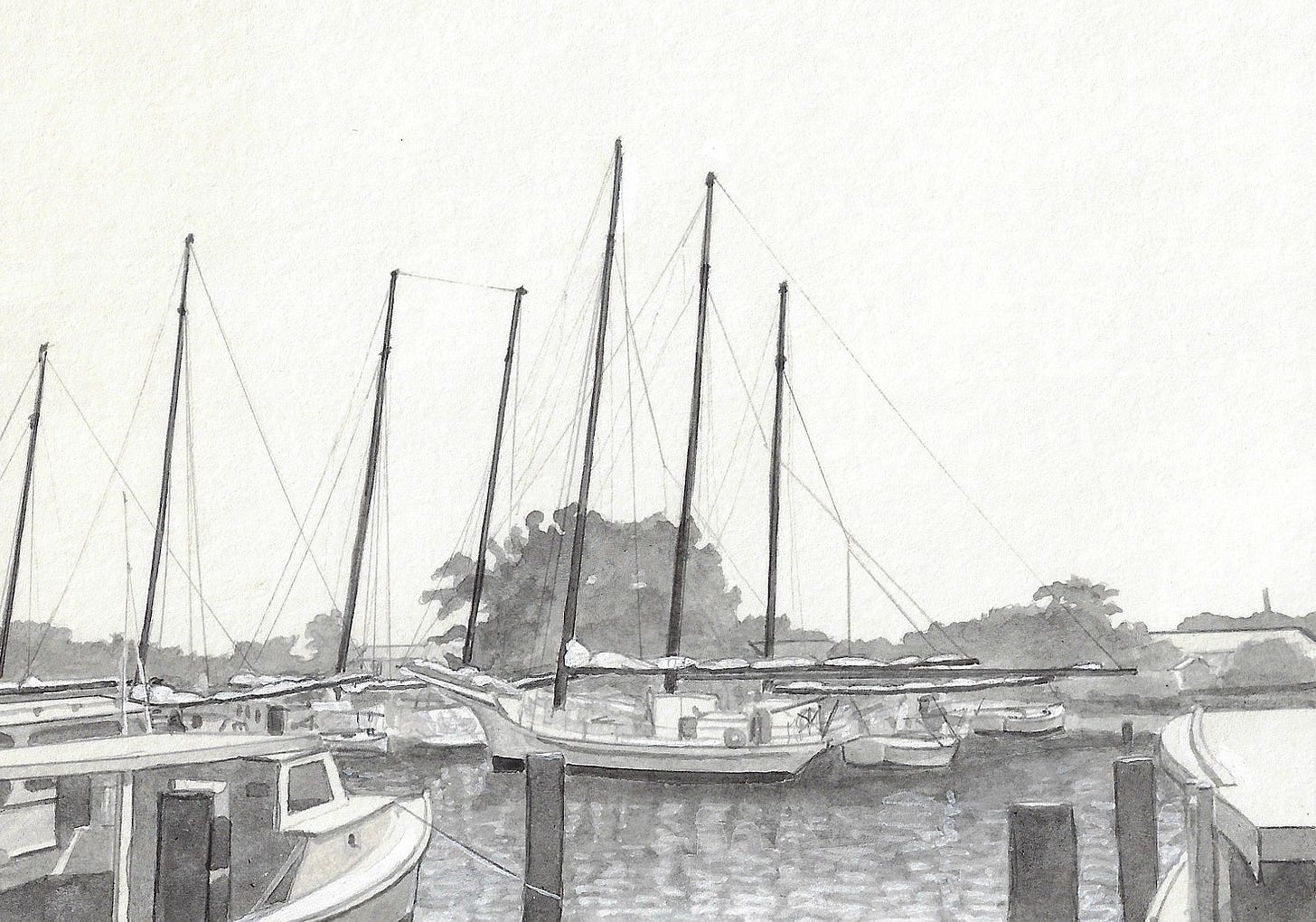

The largest remaining group of skipjacks — nine, by my count — is tied up by the drawbridge onto Tilghman’s. The skipjack is one of many specialized sailing boats once built around the Bay. Some people say that American boat design reached its highest expression on the Bay. Skipjacks are the only U.S. fishing fleet that remains under sail, and they survive because only sailing craft are allowed to dredge (“drudge” they say on the Eastern Shore) for oysters. Watermen using motors must “tong” for their oysters using a hinged pair of long-handled rakes. Either way, and whatever seafood a waterman is after, the work is hard in all kinds of weather. Crabbers rise at three or four in the morning.

Dorchester County lies halfway, north-south, along the Eastern Shore, and it appears to be as much water as it is dry land. Looking out at the distance, islands and points of land are so low that you would never notice them except for the bushes or trees they support. The water table is so high that you can’t dig far, so graveyards are located either on a rare small bulge in the terrain or the graves are topped with concrete seals. Sometimes, family dead are buried in a raised mound in the front yard. Not long ago, I drove down to a watery Dorchester village named Toddville. In that area, some of the houses exist on mere mites of land linked by road; lawns quickly taper off into swamp grasses and the line where mowing stops is arbitrary. When the easiest way to travel was by water, it didn’t matter if no road reached a house. Today in this part of the Eastern Shore, nature is still mostly unspoiled. (The classic work by a naturalist about the life of the Bay is Gilbert Klingel’s beautifully written The Bay, still in print after forty years.) In Toddville in the afternoon, all the activity was by the water. At several wholesalers, watermen were unloading crabs.

Around the Bay, where there are crabbers, there are usually shedding floats. The floats hold the peelers until they shed. Some, tended from a skiff, are shallow floating cages made of wooden slats. Most common these days are onshore “floats” erected next to the water. Many are ramshackle. Simple legs support a plywood table bordered by two-by-tens that hold the peelers in about five inches of salt water. As you lean close to watch the wondrous molting, the lively peelers scoot off sideways. Drains, pumps, and a network of white plastic pipe ensure a continuous flow of salt water. Bare bulbs allow soft crabs to be culled at night. During the big runs, when the floats are loaded with crabs, some large operations “fish up” soft crabs in shifts twenty-four hours a day. A family operation might fish up only four times a day, starting before dawn and ending just before bed at night. A minimum of every four hours is recommended.

I asked a man tending some floats near Deal Island about freshness. He said he would eat only soft crabs that had shed that day. Why? “I just would.” I don’t think it had ever occurred to him to eat soft crabs in a restaurant until I brought it up. He laughed. Soft crabs make excellent bait, and while we were talking some sport fishermen bought a dozen small ones for that purpose. The price was five dollars; a dozen of the largest were twenty. Soft crabs are sold in half-inch increments, measured tip to tip, starting with medium (three and a half to four inches) and proceeding through hotels, primes, jumbos, and whales (five and a half inches and over).

The fair-sized town of Crisfield is built largely on oyster shells, as you see in many places. The town is named for John Crisfield, president of the Eastern Shore Railroad, which in the 1870s brought tracks and prosperity to the town, making it the seafood capital of the Bay. Now the business is almost all crabs, and the old brawling waterfront is calm and partly touristy. You know when crabs are being picked by the smell of steamed crab in the air. In June, I walked in the back door of a picking house and asked to see the picking. I was pointed toward a room where several dozen Black women were sitting at stainless tables piled high with steamed crabs. With a sharp knife in one hand, each was ripping off the shell and nimbly picking the meat as fast as humanly possible. The grades of meat were kept separate. Jumbo lump looked truly jumbo. Machine-picking is a last resort during only the biggest runs; it reduces the meat to too-small pieces.

Neither the grades nor the names of crab meat are agreed upon by packers, but they are roughly three. Best are “jumbo lump” and “lump” from the muscle that operates the swimmers. Then comes “backfin” or perhaps “flake,” “regular,” or the ironically named “special,” all body meat from muscle that operates the legs. Last is the darker, stringy “claw” or the intact “cocktail claw.” Jumbo lump and lump have the double appeal of large pieces and little or no shell. The others contain smaller pieces of meat or shreds and more bits of shell. In June, the retail price was about $21 a pound for jumbo lump, higher than usual because cool water temperatures had reduced the size of the May run, and crabs still weren’t hanging onto trot-lines or moving into pots as usual.

In Crisfield, the large companies have racks and racks of vertically stacked shedding floats. The Handy Company is largest by far. Its only business is soft crabs — live, frozen, or dressed and chilled to 30 degrees F (the low temperature is an unusual approach). An old man at one of the smallest float businesses had an accent so strong that I followed only about a third of what he said. I did understand that years ago he never thought the on-shore floats would work. Like the man at Deal Island, he fishes up his soft crabs just three times a day. Roughly half of all soft crabs are now frozen, especially the weaker ones and the many that shed on weekends, when wholesale customers aren’t accepting deliveries. But about half the soft crabs are still shipped live at about 45 degrees F. They’re arranged in trays lined with seaweed, straw, or damp paper. With care, they last about four days, but the sooner they’re eaten, the better they taste.

In the search for good places to eat crab on either shore, you frequently enter Jane-and-Michael-Stern country. The Sterns are the authors of Roadfood, a guide to diners, truck stops, and other joints redolent of the 1950s and 60s. Theirs is often the land of truly awful food. Around the Bay, it includes the beloved seasoning called Old Bay. The main ingredient is celery salt, and it has some heat from mustard and red pepper. People sprinkle it over steamed crabs with amazing abandon. At a tourist restaurant like the Crab Claw in St. Michaels, directions for dismantling crabs are printed on the place mat, but if you order steamed crabs the table will be covered over instead with layers of paper. Crabs are piled onto the table, and the standard small mallets for cracking claws are provided. (I’ve heard, though, that mallets are only for “foreigners,” and natives make skilled use of a small knife.) I watched a well-dressed woman with lacquered fingernails dissect and eat her crabs with such silent sense of purpose that I would have been frightened to interrupt her. Most tables were more boisterous. The favorite Eastern Shore crab drinks are pitchers of cold beer and iced tea.

The crab soups served in restaurants can be discouraging mixtures of canned vegetables and picked crab meat, cooked forever. The cream soups are a little better, although so much flour can be used as thickening that the flour itself is a flavor in the soup. (Having tried the soups, I’ve never had the courage to move on to deviled crab.) You may clearly taste a base of chicken, which the old cookbooks never call for. Sometimes there’s a little pitcher of sherry on the table for each person to add to taste. (To be clear, the famous she-crab soup, which calls for sherry, isn’t a Maryland soup; it belongs to Charleston, South Carolina.)

Steaming is less likely than boiling to overcook crabs or make them watery. Many people around the Bay catch and steam their own. The liquid in the pot is often vinegar and water with various spices or it is beer. I haven’t been around the Bay often enough to steam any crabs, but I’m told the shells turn red first at the tips, then around the edges, and as soon as the whole shell is red, the crabs are done and should be quickly pulled from the pot.

Crab cakes are often considered the test of a crab house. Some are whammed by too much Worcestershire sauce or so oleaginous with mayonnaise that the brand makes a significant difference to the taste. Most I’ve had were better than that, but someone told me that to have the best Eastern Shore crab cakes, “Buy a pound of crab meat and knock on someone’s door.” I didn’t have the courage for that, so I’ve eaten them in restaurants and made them myself. When James Michener was doing research for his novel Chesapeake and living in St. Michaels, he raised a stir by writing a letter to the local newspaper about the ideal crab cake and assigning numerical ratings to the crab cakes he had eaten in restaurants and homes over the previous seven years. He did leave the makers of lowly cakes discreetly unmentioned. Contrary to Eastern Shore gospel, Michener liked a touch of onion. One of his informants sold six different grades of ready-to-cook cakes to restaurants; he told Michener that a really good crab cake cost so much to make that the public wouldn’t pay for it.

Almost everyone agrees on two points of an excellent crab cake. It is made only of jumbo lump or lump crab meat, mixed gently with the other ingredients to keep the pieces large, and it contains few detectable breadcrumbs or none. A light texture results. I’ll take the risk of asserting that the best way to add breadcrumbs is to soak some of the white interior of a good loaf of bread in water for about fifteen minutes, squeeze out what water will come, and mash the result to a paste. Beyond texture, certainly Maryland crab cakes should have some cayenne, or red pepper. Green and red bell pepper haven’t made many inroads in the state, but some Worcestershire and mayonnaise have become the rule. Usually, one egg per pound of crab meat is added to prevent the cakes from falling apart. And so what if one does? Butter is the tastiest fat for frying. (Many restaurants offer the revisionist option of baking in the oven.) All the cake needs is to brown and heat through. The best cake is fragile, nothing more than hot, carefully seasoned crab meat inside a crisp fried crust of crumbs.

Traditional Maryland cooking around the Bay was similar to tidewater Virginia and other Southern coastal cooking. The cooking of whites was based on that of England with significant African contributions, and some French influence for the well-to-do. Caribbean Creole influence was weaker in Maryland than farther south, and on the western shore of the Bay some dishes were borrowed from the Germans who began to settle in Maryland in the 1730s. Only families floating in the cream of society used niceties such as “sweet herbs.” Most of the old recipes rely on plain seasonings of salt, black pepper, cayenne, butter, and cream. The African-American contribution in Maryland is evident in the use of okra and eggplant. I haven’t found evidence of benne (sesame seed) or peanut soup, as in more southern places, but seasoning with cayenne is common. The historian Karen Hess interprets the Southern approach as having called for a restrained use of red pepper to produce a “brightness,” which isn’t achieved with black pepper’s more forward flavor. She points out that the written recipes we have come from affluent households and don’t convey the hand of African-American cooks. We know what the mistress wrote down, but what exactly were the cooks cooking? And how did they cook differently for themselves? Maybe with more liberal seasoning.

One book of old-fashioned Maryland food is Frederick Philip Stieff’s Eat, Drink and Be Merry in Maryland, published in 1932. Like much of the social life that persisted at that time, a good part of this cooking has died out. Stieff pointed out that “much of Maryland’s culinary supremacy is due to the kitchen skill of the early slaves and their descendants.” He meant cooks in white homes, where he sought them out for their recipes. (His book, however, has appalling racist illustrations.) He collected some recipes from restaurants, but most came from families, and almost all were still in use. They were often recorded in “age-stained family receipt books of every vintage up to and over one hundred years old.” He explained, “I have preferred to copy from manuscript, feeling that much of the charm would be lost by editing or paraphrasing.” The crab dishes include crab gumbo and other soups, crab cakes, deviled crab, crab flake cutlets, creamed crab flakes, fried soft crabs, and a restaurant’s fancied-up “imperial deviled crab.” Mayonnaise and Worcestershire sauce show up only in the restaurant recipes.

The finest Maryland cookbook is Mrs. B.C. Howard’s Fifty Years in a Maryland Kitchen, first published in Baltimore in 1873. The author was born in 1801, into an elite circle of Baltimore families, gave birth to twelve children, and lived to be eighty-nine. As a Maryland lady, Mrs. Howard preferred that her name not appear in her book, but she relented because, according to her preface, the book was published for charity, and it was thought that an anonymous book would not sell so many copies. Mrs. Howard makes free but not careless use of meats, butter, cream, eggs, and kitchen labor. Using italics, she stresses thickening with “a very little flour.” She advises that “simmering makes meat tender; boiling makes it hard.” Nutmeg and mace play exaggerated roles, including with crab, although at times she calls for only a “grate” of nutmeg or “two blades” of mace, or she counts out three individual cloves. She cooks some things longer than we might, but for one oyster soup she notes that it is better to save the best oysters to add at the last: “They then go to the table plump and large, not so much done as the rest must be to make the soup good.” She doesn’t scant flavor. In French fashion, she exploits lobster shells for sauce, and she makes her mayonnaise with olive oil. Soups are prominent.

Mrs. Howard doesn’t mention crab cakes by name, but she has similar fish croquettes and “ressoles” (rissoles), which were made up and down the Southern coast. Crab may have been a variation. It’s hard to believe she didn’t make crab cakes. The earliest recipe I’ve seen by that name — “Crab Cakes for Breakfast. (Very nice.)” — appeared in 1894 in the Maryland and Virginia Cook Book by Mrs. Charles H. Gibson of Ratcliffe Manor in Talbot County. The crab meat is seasoned “high with red pepper and salt” and held together with flour and butter. The cakes are dipped in egg, then cracker crumbs, and fried in butter or lard.

If there’s a truly great crab restaurant on the Eastern Shore, I haven’t heard of it. But across the Bay in Virginia is a chef who is — according to a friend of mine who knows something — “the best crab cook in America.” This cook is Jimmy Sneed. For the last five years he has been chef and owner of the restaurant called Windows on Urbanna Creek in tidewater Virginia, about two hours south of Washington, D.C.

From the quiet center of the town of Urbanna, a shady street heads down to the water, narrows, and takes a sharp curve past a tiny crab house and a marina before it ends in the restaurant’s parking lot. The restaurant building, inherited from an earlier venture, is a glass-walled octagon set a story in the air. The dining room overlooks the wide mouth of Urbanna Creek where it enters the Rappahannock River, about fifteen miles from the Bay. Although the restaurant’s prices are moderate, almost none of the customers are local. Nearly all drive from more populous and affluent places.

Jimmy Sneed is a large man with a full brown beard and curly hair almost to his shoulders. He worked for six years (“six long, hard years,” he clarified) under Jean-Louis Palladin at the restaurant Jean-Louis at the Watergate in Washington. Palladin is widely considered the finest French-born and -trained chef cooking in America. For another year, Jimmy Sneed worked under the highly regarded Gunter Seeger, now of Atlanta. Sneed, for a chef working at his level of quality, is informal and relaxed, and he’s happy if his customers dress casually. Once, when Jean-Louis Palladin ate at the restaurant, he suggested that there should be separate plates for vegetable and starch accompaniments. Jimmy Sneed’s response is that “the American way is to take a plate and load it up.”

His flavors are unusually direct. The name of each dish on the menu is a short description, no more than a line, so there is little room for questions. When you taste his food, his aim is: “Right away you know what it is and right away you love it.” I asked his view of crab gumbo and he answered, “It’s not me.” He finds it a confusion of flavors, too many. He uses few herbs or spices, he doesn’t marinate his meats, and he makes minimal use of wine in cooking and no other alcohol. Nearly everything comes with a straightforward sauce based on such things as shallots, mustard, capers and tomatoes, olives, sausage, or Parmigiano, often with butter. Consciously or not, the combinations seem chosen because they decline to form a synergy, an interaction of flavors that would undercut the separate distinctions of each.

The restaurant succeeds in presenting food without such subtle supports, because it treats superb materials with impeccable haute cuisine technique ( which might be defined as cooking that avoids anything, above all overcooking, that would interfere with the innate taste of the ingredients). One result is a range of perfect textures. Sneed uses regional materials because “they’re spectacular and they’re here.... Freshness is key to us.” Most items are caught or harvested on the day they are served, and the menu changes daily. Sneed prefers regional products, but he doesn’t prepare regional dishes; he seemed almost horrified when I casually mentioned “Southern” food.

As in many restaurants, garden produce is local; the off-season lack of it is the greatest limitation Sneed feels. Shiitake mushrooms are grown six miles away year-round, and there is very young local lamb. But what truly excites Jimmy Sneed is the yield of the Bay and its rivers. Besides crab, there are blowfish (“sugar toads” to local Virginia watermen, “swelling toads” on the Eastern Shore), rockfish, shad, shad roe, bay scallops, pompano, speckled trout (salmon trout), sea trout (weakfish), and cobia (“one of the best fish in the Bay”). Most come from a wholesaler who keeps a shack on a point on the Bay, where several dozen boats come to sell their day’s catch. When something special comes in, the wholesaler calls. Sneed talks to him “three to six times a day.”

The restaurant’s lump crab meat comes from Cap’n Tom eight miles up the river. He has instructions not to overcook, and as the women who work for him pick the crab, he sets aside the moistest batches for the restaurant. Sadly, there is no good bread to be had in the area and too little space in the narrow restaurant kitchen for a bakery; Sneed uses frozen dough in which you can taste the sugar. Because he wants his wine list as easily understood as his menu, the choices are entirely American, and they lean heavily on California Chardonnays. (These better, more concentrated California Chardonnays are too much for crab’s delicacy and sweetness, and the well-salted food brings out wines’ slight bitterness from oak. A Sauvignon Blanc or a Virginia wine from the list may be more to the purpose.) Jimmy Sneed isn’t doctrinaire. Good things that can’t be had nearby come from afar, such as imported farm-raised salmon and chocolate.

At the edge of the restaurant’s gravel parking lot are two small shedding floats that supply most of the restaurant’s soft crabs. One night as the restaurant was closing, I stood with Jimmy Sneed watching the peelers. One had pumped itself full of water become a buster. The back of his shell was cocked open, and he (by the shape of his apron he was a he) was slowly working his swimmers to extract them from the old shell. As we studied him, Sneed said, “The reason my soft crabs are better than anyone else’s in the world is when this buster is done I’m going to carry it upstairs.”

In less than ten minutes the crab was free, and Sneed gently picked it up and held it so I could feel its glistening softness. Crabs in this tender state are sometimes called “velvets.” They are so weak that they scarcely move, and if they are shipped, they die. Since restaurant chefs and fish-mongers will buy only soft crabs that are still alive and moving, nearly every soft crab is kept in salt water at the floats for from four to six hours until it is ready to survive the rigors of shipping. Meanwhile, shells and cartilage have begun to harden. Even the finest chefs insist on these live soft crabs. “In the effort to have good regional product they’re misguided,” Jimmy Sneed said. Most of these soft crabs are deep-fried (though menus usually say “sauteed”) to crisp the outside and the tough, papery inner cartilage, which at the same time overcooks the meat. All that matters, Sneed explained, is that a soft crab is truly soft and has shed that day. He hustles his velvets out of the water and into the refrigerator.

Back inside the restaurant, Sneed used a pair of scissors to cut off the face of the velvet just behind the eyes, and then he quickly killed the crab by stabbing its brain with the point of the scissors. (Actually, what the crab has falls short of a brain, but, contrary to most cookbook instructions, if it is intact the crab is still alive.) He squeezed out the sandbag (stomach) and the mustard-colored liver (technically, hepatopancreas), and he pulled off the apron. Then he lifted the flaps of the lax shell to snip away the dead man’s fingers (gills) on either side and also to show me the fat beneath the outer rim of the shell; it has the same color, consistency, and shapelessness as the liver. Many recipes call for discarding the fat, but it contributes a rich sea taste and texture. The liver, on the other hand, is slightly bitter and should be removed. Sneed said he believes people confuse the two and so call for getting rid of both. He leaves the fat where it is.

Among the crab dishes at Windows on Urbanna Creek are a smooth red pepper-crab soup containing the counterpoint of mouth-filling pieces of crab; crab cakes that are made with only jumbo lump meat, mayonnaise, and Meaux mustard (not so much cakes as unbreaded tapering mounds, quickly baked in a very hot oven); tempura-fried papershell claws with a sweet garlic sauce for dipping; crab-filled ravioli with seared slices of sea scallops and seaweed salad; quail stuffed with crab, Virginia sausage, and shiitake mushrooms; and soft crabs, floured and fried in clarified butter (cut with canola oil to raise the burning temperature) and brushed with lemon.

When traditional cooking and dishes disappear, as they so often slowly do, what’s left of regional food is regional ingredients. Not all local foodstuffs are wonderful, but nearly all the best food is marked in some way by the geographic idiosyncrasies of where it lived or was raised. Jimmy Sneed won’t go so far as to say that Chesapeake blue crabs taste different from other blue crabs caught up and down the East Coast, but they could hardly be better. Things often taste best when they grow in the place where they are naturally most abundant. They’re an essential part of the experience of that place. ●